Now, whilst I have recordings of Bach’s Goldberg Variations

played on both the harpsichord and piano, my recordings of the 48 Preludes and

Fugues are all played on the piano. I wondered if this meant that I, too,

couldn’t stand over an hour and a half of the harpsichord.

Much, of course, depends on the harpsichordist, the music and, indeed, the actual harpsichord used, so the answer isn’t that simple. I prefer piano performances of the ‘48’ simply because I feel that the musical line comes over clearer so long as the pianist is also capable of projecting the inner logic of the music.

This led me to think about the whole issue of period performance and the question of whether we really need ‘authenticity.’

I first came across a recording on period instruments way

back in the 1970’s when I bought a Beethoven recording by the Collegium Aureum

with Jörg Demus playing a hammerflügel

- or fortepiano. I later investigated the baroque era as well as the recordings

of early music by David Munrow (coincidently Gramophone magazine has a feature

on David Munrow in the current – April 2012- issue www.gramophone.co.uk).

Looking back at these early recordings makes me realise how far period instrument performances have come and, more to the point, how much they have influenced modern instrument performances.

In the late 1980’s I remember being absolutely stunned by the Beethoven Symphony recordings made by Roger Norrington with the London Classical Players www.emiclassics.com . These performances really blew away the cobwebs with faster tempi, a clarity that allowed the beautiful woodwind passages to come through and their sheer exuberance.

Period performance gradually made its way into later music such as Berlioz and Brahms and, again Roger Norrington knocked me flat.

However, time is a great leveller and with David Zinman’s recording of the Beethoven symphonies with the Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra on Arte Nova www.sonymasterworks.com something new had been injected into modern instrument performances. It was not only the new Barenreuter edition that was used by Zinman, it was also the livelier tempi, period style use of timpani and a feeling of rediscovery.

It was at a concert at Symphony Hall, Birmingham where I heard the late Sir Charles Mackerras conducting Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony, that I realised how much the period instrument movement had affected modern performances.

Sir Charles had of course conducted period instrument orchestras and this showed not just in the style of playing but in the use of instruments. Within the ranks of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra were natural horns and timpani using the harder hammers to give a period ‘thwack’ to the sound.

This was one of Sir Charles’ last concerts so I feel privileged to have been present to hear such a memorable concert when, despite his years, he gave a wonderfully vibrant and exciting performance.

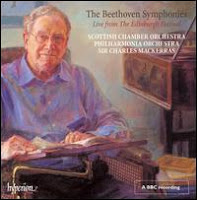

Since then I have looked more closely at his last recordings

of Mozart and Beethoven.

|

| Hyperion Records CDS 44301/5 |

|

| Linn Records SACD CKD 308 |

|

| Linn Records SACD CKD 350 |

Mackerras’ five CD Beethoven cycle on Hyperion was recorded live at the 2006 Edinburgh Festival. Right from the start with symphonies number one and two these are joyous performances with rhythmic tempi, fast at times, but not rushed. Climaxes are pointed up with thunderous timpani and there is a transparency that allows the brass and woodwind to shine through. The orchestral control is superb as they follow every nuance of Mackerras’ direction.

Just listen to the third symphony with crisp, precise

playing from the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. There is poetry in the

thoughtfully paced second movement funeral march. Whilst the horns are not

natural horns they make a wonderful rasping sound.

Symphony number four doesn’t disappoint, with a taut finely

paced performance. Mackerras seems to find the natural pulse in Beethoven so

these tempi just seem right. Symphony number five is not in any way hysterical

or overblown. The music is allowed to speak for itself. The transition from the

third movement scherzo to fourth movement allegro – presto is perfectly drawn.

Early sketches show Beethoven planned a three movement work at one stage.

If anyone still thinks that Mackerras’ tempi are too fast,

then listen to the opening of Symphony number six, a true allegro non troppo. The

storm sequence in the fourth movement is not a violent one but effective

nevertheless. The finale is beautifully realised.

The seventh and eighth symphonies have a light touch with number seven played with a confidence and swagger. The performance of number eight brought out so much that is new that I went back to Karajan’s 1962 recording for comparisons. In many ways number eight is the finest of the cycle bringing, as it does, such insights.

For the ninth symphony Mackerras changes to the Philharmonia Orchestra, an orchestra that, like the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Mackerras had close links with.

It may be heresy, but the Choral is not my favourite Beethoven symphony. However, this performance is such that it raised my appreciation of this great work. After the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, the sound of the Philharmonia in the first movement sounds positively huge. The slow movement is beautifully done. The soloists for the choral finale are well chosen and make a fitting conclusion to this fine cycle.

Adopting period style for its own sake is not a guarantee of good performance but in the hands of a master like Mackerras the rewards are immense. These performances are full of stature and should be in anyone’s collection.

The recordings made in the Usher Hall, Edinburgh are excellent. There is no obvious audience noise in first four CD’s but in the ninth there is some slight noise between the movements. There is a good amount of space around the orchestra and great instrumental detail. Applause is edited out.

It was Mackerras’ performances of Beethoven that led me to listen to his Mozart. In the Linn recordings you have symphonies number 29, 31, 32, 35, 36 and 38-41 thus giving you all the later symphonies. www.linnrecords.com

Played by the Scottish Chamber Orchestra again, these performances show an equal regard for period performance practice. These are agile performances with dynamic contrasts, period sounding brass and prominent timpani. These are joyous readings with wonderful orchestral balance and transparent textures. As in Mackerras’ Beethoven, the poetry in the slow movements is beautifully revealed.

The Jupiter symphony in particular shows all the sparkle and grandeur of this wonderful culminating symphony. These are performances that show Mackerras’ lifelong knowledge and wisdom with Mozart.

With first rate sound these two discs should not be missed.

But what of period performance itself? Well, I prefer to

have my cake and eat it, enjoying both period and modern instruments. Surely it

is the musicianship that counts more than anything and, in the case of Sir

Charles Mackerras, that is what you get in spadefuls.

No comments:

Post a Comment